The experience of the defeat of gasohol woke the chemurgists to the political realities they were facing and led to the formation of the National Farm Chemurgic Council in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1935. Funds came from Henry Ford, who provided facilities for the first conference; from Ed O'Neal's American Farm Bureau Federation and from Garvan's Chemical Society.

What was at stake was of fundamental significance. The battle determined the course the century would take regarding the primary source of fuels and raw material for industrial economies. The amassing political power of the agrarian portions of the country threatened legislation which would mandate the use of agricultural inputs in fuels. If that effort succeeded, other pro-agriculture legislation would surely follow including more mandates in favor of agricultural alternatives to petrochemicals. The stakes were enormous. Those who stood to lose resorted to any tactic, including such subterfuge as the Farmer's Independence Council, an ostensibly pro-farm organization:

O'Neal branded these men "Wall Street hayseeds" in the Farm Bureau Newsletter of May 20, 1935. Later they were caricatured on the front page of the Newsletter (April 28, 1936) as "The Farmers in the Dell." Pew, du Pont, Sloan and others were shown on Wall Street in overalls and top hats, entering the office of the Farmers' Independence Council.

A pamphlet issued by the Council, which went out of existence soon after the Senate exposure, is of historical interest for two reasons: first, some of the same financial backers are still trying to influence farm policy; and second, the phraseology of the pamphlet is similar to that of many of the organizations in which they still participate. The pamphlet, issued in 1935, was entitled "The Truth Shall Make You Free" and included:

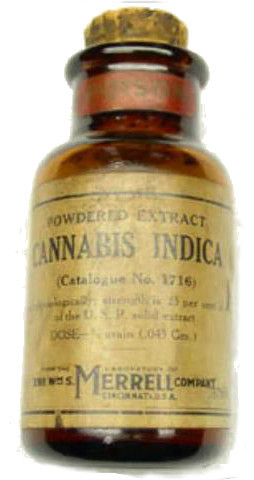

During this same period, stories were appearing in the popular press concerning marihuana, said to be the same as hemp. Among African-American, Hispanic and South Asian minorities, the use of cannabis genotypes that produce copious psychoactive resin was popular. In India, where alcohol was illegal, cannabis use was common and ancient, a sacrament for some religious sects. Hashish production in India was under government control. However, Western society was unfamiliar with it and it was not the choice of the dominant class. There was no political force to resist the imposition of a new prohibition.

The prohibition of plants alien to Western society was hardly a new phenomenon. In the eighteenth century, coffee was the rage and was similarly received by the powers-that-be:

The 1937 Marijuana Tax Act was, in fact, not a prohibition. The prohibition of alcohol had required a constitutional amendment. The MTA was something subtler. To understand its intent, it is necessary to look elsewhere than either the traditional hemp industry in Kentucky and Wisconsin, or the traffic in Mexican marijuana. Because, whereas the industry in Wisconsin amounted to less than 1500 acres during the Thirties, there was a sudden expansion at this time in hemp being grown by a new group of entrepreneurs, principally in Minnesota. They had a new idea, a chemurgic idea: besides the fiber, hemp could be a source of cellulose.