Civil War hero, Governor of Wisconsin and first* Secretary of Agriculture, Jeremiah Rusk is buried under a Washington-monument style gravestone in the cemetery in Viroqua, Wisconsin. This native son of my own hometown brought a certain august and historic presence to the county seat of Vernon County and it may be one of those ironic twists of fate that, growing up there as I did on Rusk Street, while knowing little of the dignitary in the cemetery, I would later in life find myself carrying on an endeavor that Rusk had started during his brief tenure at the nascent USDA.

I like to imagine that this veteran of the War Between the States, at some point in his military career, might have taken pause to reflect on the factors that underlay that carnage and concluded that one matter in need of redress was the nation's dependence on a single overarching and domineering source of fiber, that coming from the Southern States, now stained with the blood of the Nation's youth. Was there a moment, perhaps, when Officer Rusk sat upon his steed gazing in anguish at the wasted lives whose blood had been spilled ostensibly over the moral issue of slavery, but fundamentally over control of and access to a fiber crop, was there such a moment when he resolved to promote the agriculture of fiber plants adapted to the northern latitudes?

I imagine him taking a vow at that moment to dedicate himself to promoting the northern "bast" fiber crops because years after he was Wisconsin's Governor and immediately upon becoming the first* US Secretary of Agriculture in 1890, he inaugurated of the USDA's Office of Fiber Investigations.

Although he would not live long enough to see its progress (he died shortly after, in 1893), for the next four decades this office would expend resources on the development of fiber flax and hemp, the traditional fibers of temperate cultures. The direct consequence of this initiative was the emergence of the hemp industry in Wisconsin. Although its dimensions never became large in comparison with the major crops, it did manage to survive until 1958 in the face of progressively adverse circumstances. The emergence and growth of this industry can be credited to the vision of a small group of men, beginning with Rusk. But in the end, the vision went unfulfilled and hemp disappeared from American agriculture. [Note: The author, whose "real" profession is plant breeder, not historian, directed the Hawaii Industrial Hemp Project (1999-2003), a minor skirmish in the larger struggle to return this crop to US agriculture.]

In 1890, Rusk appointed Charles Dodge to head up the new office. The situation they faced was a fiber shortage, much as we do today [1998]. Whereas today we are witnessing across the nation the bankruptcy of newspapers that have seen the cost of newsprint double in eighteen months, in 1890, the pressure came as a consequences of the newly invented grain binder. The ingenuity of the McCormick brothers had produced a machine that cut the grain-ladened stems of wheat and bound them in sheaves for later threshing. And for the binding, they required binder twine.

The twine binder brought about the final evolution of the harvesting machine. John F. Appleby, Jacob Behel and Marquis L. Gorham were the pioneers in developing the twine binder and knotter. Imported Manila jute and sisal were woven into balls of binder twine and sold to every farmer who owned a binder. The twine binder, called a "self-binder," more than any other single machine enabled the farmers to expand their wheat crops.

In 1882, the McCormick Company, having turned from wire binders to twine binders, sold over fifteen thousand twine binders. The twine binders with their automatic knotters made possible the rapid extension of the wheat belt into the West and Northwest; and large scale farming became common practice in those areas. Schager cites one farm near Casselton, North Dakota, on which sixty self-binders were employed as early as 1882.

The nation was importing substantial volumes of tropical fibers—sisal and jute–while the capability was well within reach to produce this fiber domestically. In fact, from domestically grown hemp could come a fiber greatly superior to those being imported. Charles Dodge wrote in his first report, "There is no reason why hemp culture should not extend over a dozen States and the product used in manufactures which now employ thousands of tons of imported fibers."

Writing to Dodge in 1890, one binder manufacturer testified:

There is no fiber in the world better suited to this use than American hemp. It is our judgment, based on nearly ten years' experience with large quantities of binder twine each year, that the entire supply of this twine should be made from American hemp....There are 50,000 tons of this binding twine used annually, every pound of which could and should be made from this home product.

Let's get a little perspective on this crop.

Hemp, by 1890, was probably the oldest of the Old World crops in the "New" World. Because of the critical role played by its rot-resistant fiber in the maritime activity of the Europeans, hemp traveled with the explorations. The first recorded planting in the western hemisphere was in Chile as early as 1545. It was reportedly planted in today's Canada by 1607 and in the American colonies by 1627.

Ships were rigged with hemp cables and as such it was a strategic resource upon which navies and the military power of naval empires depended. For that reason, laws were enacted in Europe and the Colonies requiring farmers to allot a portion of their acreage to hemp. After Independence, hemp was one of the farm products with which taxes could be paid in the new States.

The origin of hemp as a crop traces to the mists of prehistory in central Asia but no wild progenitor species is found today. It was the Chinese who first developed hemp as a fiber crop, as far as we know. It is in their records that we have the first historic report of the fiber used in textiles.

In Europe, where flax and wool reigned as the principal textile fibers before the advent of cotton, hemp was most often employed for cordage and for coarse canvas ("canvas" and "cannabis" have the same etymological root).

At Chatham, England, just down the Thames from London, where the British navy was built, Russian hemp was processed in Hemp Houses 1, 2 and 3. Now a Historic Preservation, the rope making technology that processed Russian hemp into hausers, marlines and anchor cables can still be viewed today.

Russian hemp was preferred by navies. Being a strategic material, hemp was the object of military campaigns waged to restrict Britain's access to the Russian hemp fields. A ship like the USS Constitution would have sixty tons of hemp in its riggings. American grown hemp tried competing with Russian hemp but was not well-accepted by the US Navy:

In 1824, domestic hemp was pitted against Russian hemp by rigging the USS Constitution on one side with American and the other with Russian grown hemp, "and after being thus worn for nearly a year, it was found, on examination, that the Russian rope, in every instance, after being much worn, looked better and wore more equally and evenly than the American."

The captain reportedly did say it was a close match.

In the States, hemp's principal role was for burlap and canvas (or "duck") and twines of various dimensions. Hemp textiles were coarse and were relegated to use by slaves in the antebellum South where "Kentucky Jeans" presaged the Gold Rush Forty-Niner's rugged, riveted hemp pants made by Levy Straus from sail-cloth and Conestoga canvas.

Kentucky is the state most often associated with hemp as it was there—first planted in 1775–that the crop reached its greatest dimensions in the nineteenth century. Kentucky's hemp farmers prospered for a time while hemp was in high demand for burlap bagging cloth to cover cotton bales and for the ropes to bind the bales under high pressure. But after the Civil War, imported jute produced with cheap coolie labor in the East Indies and imported to the mills on the East Coast usurped hemp's cotton market. Iron bands replaced hemp for binding the bales. At the same time, steam-power replaced sails in maritime traffic. After 1860, Kentucky acreage was increasingly taken by lucrative tobacco.

A small industry had transplanted itself to Missouri in the 1830s. We are told that outside a hemp mill in Lexington, Missouri, in 1861, Rebel forces successful defended themselves from behind large bails of Missouri hemp, soaked down to prevent their attackers from setting them ablaze.

But with the end of the war and the loss of slave labor—on which hemp had depended as much as cotton–hemp agriculture also declined in Missouri. When, in 1872, under pressure from the eastern manufacturers, the tariff that had protected domestic hemp and flax was repealed, the crop declined to a "niche" status.

The prospects for hemp were restricted by the labor required to extract the fiber. Hemp is not a difficult crop to grow: once it is planted, it requires no further care until harvest. For fiber, the seeds are sown close together, broadcast or drilled in rows only four inches apart. This density keeps the stems small and prevents branching, critical to high quality long fiber. So thick and impenetrable is a crop of hemp, that the dense shade under a hemp canopy prevents weed development and it is an often-attested-to benefit of growing the crop that it will clean fields of recalcitrant weeds.

But once the crop is ready for harvest, when the male plants (hemp is dioecious, that is, it has separate male and female plants) begin to shed pollen, the tables turn and it demands substantial labor. The crop must be cut and shocked to dry. Then it is spread on the land for a period of a few weeks, depending on weather conditions, to ret. Retting is the process universal to bast fiber processing whereby the fiber in the bark is loosed from the inner woody core of the stem. This is accomplished through the action of moisture and bacteria that digest the fiber binding pectins. Judging the retting process is an art requiring experience to get it just right: too little and the fiber will not separate adequately from the core (the "hurds"); too much and the fiber loses strength.

In the old, hand-labor way of handling the crop, once retting was complete, the hemp was again gathered and taken to the brake, or the brake was moved from stack to stack. The retted stems were placed across the slats of the brake and broken by pinching them forcefully between the hinged upper and lower slats. The hurds fell out under the brake and were shaken free by whipping the fiber over the brake.

Further cleaning was accomplished by the tedious repeated combing of the fibers through a pin-cushion block of long needles, a process called "hackling." The fibers were then bound in "hands," knotted on the end and transported to the mill for further refining before being ready to spin into yarns and subsequently twisted into twines and ropes.

This is how the crop was handled in Kentucky.

When Charles Dodge's Office of Fiber Investigations turned to hemp, the first priority was mechanization of these labor intensive processes: cutting, scutching (breaking) and hackling. A breakthrough in cutting the crop was made in Nebraska where the crop was gaining acceptance near Havelock:

In Nebraska, where the [hemp] industry is being established, a new and important step has been taken in cutting the crop with an ordinary mowing machine. A simple attachment that bends the stalks over in the direction in which the machine is going facilitates the cutting...The cost of cutting hemp in this manner is 50 cents per acre, as compared with $3 to $4 per acre, the rates paid for cutting by hand in Kentucky."

In the Havelock and Fremont areas of Nebraska today, the now-feral hemp provides an important ingredient to the diet of the state's chief game bird, the pheasant. The eradication campaign has largely left it alone and it is one of the significant germplasm deposits we have of Kentucky Hemp. [The author no longer believes the feral hemp stands of Nebraska trace to the short-lived hemp agriculture as stated here. Rather, it is likely that this hemp predates this period and is the remnant of an effort to get Native Americans to grow hemp in the 1840s. Although a fascinating episode of hemp history, it is outside the purview of this article. It should be noted, however, that if this is correct, then this germplasm also predates the importation of Chinese hemp that gave rise to the Kentucky variety.]

The mention of germplasm sets the stage for the introduction of the next key individual in the fortunes of the hemp industry this [20th] century: Dr. Lyster Dewey, appointed by Dodge to lead the hemp project at the USDA. His first task was to gather a collection of the world's hemp germplasm. In 1901, in the article on hemp in that year's USDA Yearbook of Agriculture, Dewey described the range of fiber hemp varieties:

...that cultivated in Kentucky and having a hollow stem, being the most common. China hemp, with slender stems, growing very erect, has a wide range of culture. Smyrna hemp is adapted to cultivation over a still wider range and Japanese hemp is beginning to be cultivated, particularly in California, where it reaches a height of 15 feet. Russian and Italian seed have been experimented with, but the former produces a short stalk, while the latter only grows to a medium height. A small quantity of Piedmontese hemp seed from Italy was distributed by the Department in 1893, having been received through the Chicago Exposition....

The Kentucky germplasm Dewey refers to was an American landrace. "Landrace" can be defined as "an agricultural crop variety reproduced locally and being of common generic type throughout the region." Kentucky hemp had developed by natural and artificial selection in the United States over the preceding approximately fifty years. It was unique.

Prior to 1850, the hemp grown in the New World was of European origin. Shortly after 1850, missionaries in China sent seeds of Chinese hemp home and it was found to perform better in the Kentucky area. It was then that the Chinese bloodline met the European and a hybridization occurred. Dewey writes that the farmers were reluctant to throw out the mixed types because they gave higher seed yields. This, of course, would have been the direct consequence of hybridity.

(Coincidentally, during this same period, two previously separated races of corn [maize] were also meeting in the expanding American grain belt. The flint-dent varieties that resulted from the merger are the basis of today's hybrid corn productivity.)

Dewey began actively breeding hemp varieties around 1912. Prior to that, the USDA focused its hemp effort on testing the crop in new environments and overcoming the mechanization hurdle. Trials were first conducted in Wisconsin in 1908, at Waupun, Mendota and...

...Viroqua!

It must be this latter site Dewey is referring to in the 1913 Yearbook when he tells how

In one four acre field in Vernon County, Wis., where Canada thistles were very thick, fully 95 per cent of the thistles were killed ...

Governor Rusk would have been proud.

At this point, the next figure enters the stage: from the University of Wisconsin's Agricultural Experiment Station, Dr. Andrew Wright. The development of the Wisconsin hemp industry is one among several accomplishments that must be credited to the leadership of Andrew Wright. Another is the invention of the corn dryer for the hybrid seed industry.

Wright realized that not only must the industry be mechanized, but the mills must be located with railroad access. And the transport distance from field to mill should be short, because a load of retted stalks is not dense. The conditions were satisfied in the fertile, lake bed terrain of east central Wisconsin, around Ripon, Waupun, Brandon and Markesan. By this time, Wisconsin had extensive rail coverage threading these towns. Rail access was available on the Wisconsin Central Railway, a subsidiary of Canadian Pacific.

Wright reported that farmers who had observed the USDA trials at Waupun were particularly impressed by the crop's ability to clean the fields:

At Waupun in 1911 the hemp was grown on land badly infested with quack grass, and in spite of an unfavorable season a yield of 2,100 pounds of fiber to the acre was obtained and the quack grass was practically destroyed.

Praise for the positive agronomic attributes of hemp are always found in discussions of the crop. In what could be the quintessential declaration of the "Hemp-Will-Save-the-Planet" movement, Dewey wrote in his seminal 1913 Yearbook of Agriculture hemp monograph:

Hemp cultivated for the production of fiber, cut before the seeds are formed and retted on the land where it has been grown tends to improve rather than injure the soil. It improves its physical condition, destroys weeds, and does not exhaust its fertility.

Unfortunately, of course, today it's illegal to grow.

Hemp's strategic role meant the crop was favored by war, and the Wisconsin industry was able to catch a wave after 1914. In a scenario that would be repeated again in twenty-five years, the crop brought a good income that encouraged investment in mill facilities. But with the cessation of hostilities, the market collapsed. The Wisconsin Hemp Order was formed on October 17, 1917, at Ripon, "to promote the general welfare of the hemp industry in the state." A drought in 1918 was a further setback. Hemp acreage declined.

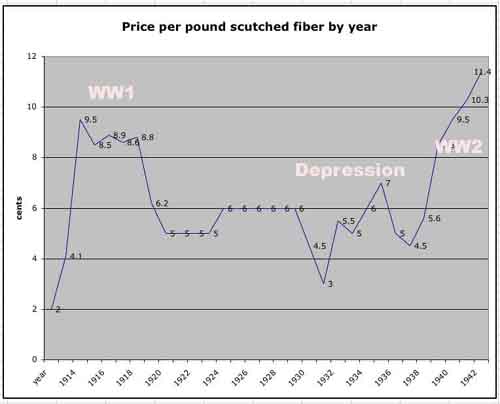

The vicissitudes of the industry are reflected in the annual average price received for fiber (Table 1.)

Wis. Dept. Ag Stat Reptg Service. 1944.

In 1918, Wright surveyed the progress the hemp industry had made in less than a decade:

When the work with hemp was begun in Wisconsin, there were no satisfactory machines for harvesting, spreading, binding, or breaking. All of these processes were performed by hand. Due to such methods, the hemp industry in the United States had all but disappeared. As it was realized from the very beginning of the work in Wisconsin that no permanent progress could be made so long as it was necessary to depend upon hand labor, immediate attention was given to solving the problem of power machinery. Nearly every kind of hemp machine was studied and tested. The obstacles were great, but through the cooperation of experienced hemp men and one large harvesting machinery company, this problem has been nearly solved. The hemp crop can now be handled entirely by machinery.

Wright was able to boast that "Wisconsin has...more hemp mills than all other states combined." And, in 1921, the USDA observed, in congratulatory tone,

The organized hemp growers of Wisconsin, working in cooperation with the field agent of fiber investigations [Andrew Wright], have so improved the quality and standardized the grades of hemp fiber produced there that it has found a market even in dull times. The hemp acreage in that State has been kept up, although there has been a reduction in every other hemp-producing area throughout the world.

In addition to mechanization of breaking and hackling the retted stems, and the recognition of the importance of rail access to the mill, there are two other innovations that contributed to the success of the operation. First, when the stalks came from the field to the mill they were damp and, for the breaking to be successful, they needed drying to below 13% moisture. This was accomplished by conveying the stems down a long, heated drying tunnel leading to the scutching machine. The byproduct of fiber separation, the hurds, was burned as the fuel source. The hurds account for 75-85% of the weight of the stalk and a great abundance was generated at the mill. What wasn't burned was given away to farmers for bedding. The hurds are highly absorbent and make excellent bedding for farm animals (except possibly chickens, we're told).

The other innovation was the recognition that the greatest yields could be obtained growing seed produced in Kentucky, rather than attempting to developed seed production in Wisconsin. The reason has to do with the photoperiod response of the crop. Since the stem fiber is the desired product, maximum yields are achieved if the crop does not shift into its reproductive mode, but continues longer in the vegetative state. When the shift to flowering occurs, the crop is cut. Since hemp is stimulated to initiate reproduction by the length of the night period, where nights are shortest (further north in the temperate summer) flowering will be delayed. A variety that will give seed in Kentucky will flower late in Wisconsin. Thus, a symbiosis developed between seed producers such as the Woodford-Spears Seed Company in Paris, Kentucky, and B. F. Brent in Lexington, and the Wisconsin companies, notably, the Rock River Valley Hemp Mills in Waupun and the Rens Hemp Company in Brandon.

Fortunately, the Woodford-Spears Company in Kentucky never threw away a single piece of business correspondence. Now included among the treasures of the Kentucky Hemp Growers' Cooperative Museum and Library, the boxes of correspondence contain letters from the Wisconsin companies such as that from Mr. G. Greenfield of Rock River Valley Hemp Mills, dated April 30, 1917, inquiring on the prospects for 2000 bushels of seed, to which E. F. Spears replied that they did not have sufficient stores. (Click here to see this letter.)

Seed is hemp's Achilles' heel. One of the keys to the failure of the industry to expand more aggressively may be the difficulty of producing adequate planting seed. The seed crop was more susceptible to the vagaries of weather, and where it was raised, in the valley of the Kentucky River, it was occasionally flooded out.

In 1928, Wisconsin saved the precious Kentucky germplasm when the seed crop in Kentucky was lost:

An exceptional flood of the Kentucky River in June and early July, 1928, destroyed nearly all of the seedhemp crop. Fortunately, Wisconsin hemp growers had seed left over from previous years, but studies on hempseed germination conducted in 1927-8 indicated that most of the seed more than 3 years old germinated very poorly.

Kentucky hemp was a dioecious variety, the normal botanical condition for Cannabis. Only half the seed would give rise to seed-bearing (female) plants. "Under favorable conditions," Dewey wrote in 1913, "the yield of hemp seed ranges from 12 to 25 bushels per acre. From 16 to 18 bushels are regarded as a fair average." (A bushel of hemp seed weighs 44 pounds.) Superfluous male plants were usually removed from seed fields by hand to reduce competition with the females. It only takes a few males to pollinate an entire field. In his diaries, George Washington, an avid hemp farmer, described removing males from his hemp seed field, an entry some have misinterpreted.

The American hemp, known as "Kentucky hemp" had developed out of the Chinese-European mix largely through natural selection for adaptation to local growing conditions and with only light direct selection for improved fiber yield and quality by the seed producers. Dewey stresses that the hemp "ran-out," if it was not renewed with new imports from China and care in the seed production to rogue undesirable types. Breeding improved varieties was Lyster Dewey's mission at the USDA.

Some emphasis was initially given to developing varieties that would flower in Wisconsin, so that Wisconsin could handle its own seed needs. But as the symbiosis with Kentucky progressed, they must have recognized its value.

One of the early varieties, named Ferramington, was developed by crossing a Chinese accession with the quality Italian type from Ferrara. It was reported to give good seed yield as far north as Wisconsin. This variety was still extant in 1943 when University of Wisconsin student Kenneth P. Buckholtz wrote his doctorate, "Breeding Techniques and Narcotic Studies with Hemp" but is now apparently lost.

The jewel of Dewey's breeding program was the variety Chinamington that broke all previous yield records. The author was told by the Hungarian hemp breeder, Ivan Bocsa, that his mentor, Dr. Fleischmann, had received Chinamington from Dewey. It was the best the world had seen to date and its yield performance was not rivaled for decades. Dr. Bocsa also told the author that Chinamington was one side of the first hybrid. Kompolti, the Hungarian variety of Italian lineage, was the other. Unfortunately, their collection no longer has Chinamington.

And we no longer have a collection.

All of Kentucky hemp and the products of Dewey's breeding program have been lost, or reduced to "ditchweed" where they are in peril of the eradication squads.

During the Twenties, the mills on the east side of the State kept up their business. For a brief time, a mill owned by the Chicago Hemp Company of America also operated on the west, in the town of Roberts. The Roberts centennial album contains a photo of a local grower cutting his hemp.

The enduring activity was in the east. Matt Rens of the Rens Hemp Company has been called the "America's Hemp King." He and his son, Willard, and son-in-law John De Boer, ran several mills in the Markesan-Brandon area south of Ripon. Their scutched fiber was shipped to Boston, not processed into finished goods in Wisconsin.

As the Great Depression settled on the country, hemp, like all farm commodities, saw its value drop, reaching the low of three cents per pound in 1932. While reflecting on this loss to his subject in the 1931 USDA Yearbook of Agriculture, Dewey provides us with an exhaustive list of the specific uses for the fiber:

Wrapping twines for heavy packages; mattress twine for sewing mattresses; spring twines for tying springs in overstuffed furniture and in box springs; sacking twine for sewing sacks containing sugar, wool peanuts, stock fed, or fertilizer; baling twine, similar to sacking twine, for sewing burlap covering on bales and packages; broom twine for sewing brooms; sewing twine for sewing cheesecloth for shade grown tobacco; hop twine for holding up hop vines in hop yards; ham strings for hanging up hams; tag twines for shipping twines; meter cord for tying diaphragms in gas meters; blocking cord used in blocking men's hats; webbing yarns which are woven into strong webbing; belting yarns to be woven into belts; marlines for binding the ends of ropes, cables and hawsers to keep them from fraying; hemp packing or coarse yarn used in packing valve pumps; plumber's oakum, usually tarred, for packing the joints of pipes; marine oakum, also tarred for caulking the seams of ships and other water craft.

Virtually all the uses for the crop are variations on a theme: twine. But the original notion of hemp as a binder twine was not fulfilled. Imported sisal kept this market as hemp continued to have difficulty competing on price. Hemp is a strong fiber, but it remained expensive and tended to serve specialty markets where its strength was needed and valued.

From the Woodford-Speers archives we have evidence of the moment of truth that arrived after the first flushed years of the industry during The Great War. In correspondence date January 2, 1917 from a Mr. Daniels, Manager, Fiber Dept., International Harvester Company of New Jersey, we see that hemp fiber is still not competitive, especially that from Kentucky.

Dear Sirs:We have your favor of the 30th ultimo.

There is no probability of our using any American Hemp grown in Kentucky during the coming season. We should be glad to do so if the quantity which is grown were greater and the price not prohibitive. However, there is and will be a demand for more than you can possibly produce in Kentucky for products which can afford higher priced material than can be afforded in the manufacture of binder twine and in all probability, as Sisal goes up your Kentucky Hemp will go up correspondingly high.

We are deeply interested in the increased production of American Hemp and are making some experiments in northern Illinois and also in Wisconsin where land values and other conditions are not any more favorable for cheap fibre than they are in Kentucky, but these experiments are being made in this locality in consequence of being conveniently near our shops where the work on Hemp machinery must be carried on. If we succeed in getting a line of machinery which will handle this Hemp successfully, it is our intention to develop the extensive growth of this plant in localities where land is very cheap. We may not get the very excellent quality of fibre which you people grow in Kentucky, but believe that we can get a fibre which will be In every respect suitable for binder twine and grow this fibre at prices which will fairly compete with Sisal and Manila even under ordinary circumstances.

In April, Mr Daniels writes again to Spears, this time to order seed "in as large quantities as you find possible" at $5.00 per bushel.

The vision of binder-twine hemp went largely unfulfilled. Cheap tropical fibers sufficed. Markets were not diversifying or expanding for the Wisconsin crop, and on the horizon great clouds were looming. Each of the dramas that cut across hemp's path like black cats are manifestations of enormous societal transformations taking place in the lull between the wars. The tide of de-agrarian-ization that had been rising slowly from the last century with the growth of the synthetic chemical industry, swept through in "The Chemist's War," and continued unabated. The chief market for this industry was explosives, textiles and agricultural chemicals. The critical decade was the Thirties. The pressure applied by synthetics to the gamut of natural fibers was transmitted down the line. Cotton, the staple of the southern economy, used its considerable political clout to pull USDA fiber research dollars into conquering its problems, of which there were many. The result was a completely chemically-dependent crop that today is estimated to use 25% of all the chemicals applied in agriculture to control its weed and insect problems.

With the conversion in 1933 of Rusk's Office of Fiber Investigations into the Division of Cotton and Other Fibers, and the termination that year of Lyster Dewey's hemp breeding program, the curtain descends on the Governor's vision of northern fiber industries.

Yet, it is at this time when the story begins to truly heat up as hemp moves from the margins of agriculture into the three ring circus of politics. Matt Rens went to Washington in 1937 to testify before the House Agriculture Committee's Hearing on Marihuana. It had come as a surprise to farmers and processors alike to learn their weed-controlling crop was the Assassin of Youth.

Yet, the truly sordid history of marihuana prohibition managed to pass by the Wisconsin industry, and, as Andrew Wright told the chemists at the Federal Bureau of Narcotics' Marihuana Conference in 1938, the growers in Wisconsin "are not concerned about this last law [The 1937 Marihuana Tax Act] because I believe they were given a very square deal in the national legislation on the matter."

The deal was a recognition that hemp fiber had no potential to be diverted into the recreational drug market. Marihuana, in that law, was defined as the flowering tops of the hemp plant. In truth, it is the flowering tops of female, non-fiber Cannabis sativa L. varieties from equatorial regions. Fiber hemp never had psychotropic potential, but that is for another discussion. The modifications made to the original draft of the tax law allowed the industry to continue its "legitimate" operation. The law gave the Treasury Department's revenue agents the power to entangle business operations in redtape, if they chose. In Wisconsin they did not so choose. In Minnesota, they did. The industries in Illinois and Minnesota that the FBN strangled with inspections in the Thirties were different from the Wisconsin industry. They were interested in cellulose and paper. But this, also, is another story.

The industry in Wisconsin was not the target of the FBN's campaign against marihuana. When Japan moved against our fiber plantations in the Philippines, domestic hemp became strategically important again and Wisconsin was the major site of the War Hemp Industries emergency hemp mill construction. Mills were built in Cuba City, Darien, Union Grove, Hartford, Ripon and De Forest. Of the 42 mills erected at a price tag of nearly $300,000 each, Wisconsin had the greatest number of any state. Andrew Wright is said to have had a hand in their design. Wherever one encounters a war hemp mill, whether in Ripon, Wisconsin, or Winchester, Kentucky, the architecture is the same: concrete block construction with arched roof and the long drying tunnel (Figure 2). They appear as though built to withstand enemy barrage. All the mills in Wisconsin, but for the one in Cuba City, are still standing solid and housing an industry. (The old buildings of the Cuba City mill are dilapidated, but standing [1998].)

| Location | Today |

| Ripon | cattle auction |

| De Forest | manufacturing |

| Darien | foundry |

| Union Grove | foundry |

| Hartford | manufacturing/warehousing |

Drawing by Joe Strobel

The war investment in the local hemp industry was a boon to these areas. The Union Grove Sun kept tabs on the progress of their mill: it began operation on March 17, 1944. In July, the Sun reported, "The employees of the Union Grove mill are practically all from localities near to Union Grove and to their efforts and loyalty, credit is given for the fine record of this mill to date." The Navy was extending its fiber stores by mixing in 10% of the war emergency domestic hemp.

The problem they faced was shortage of labor. A solution is reflected in a feature still found at the Hartford mill, where the catwalk remains from which guards watched over the German POW laborers. The POWs were one answer; another, the Sun records:

Plans are being made for the start of night shift in the very near future. The help for this second shift operation will come largely from the Relocation Centers for Californian Japanese. Already, seventeen of these relocated Japanese have arrived and are being housed at Kansasville.

But then after very few months operation, the circumstances of the war shifted and the mills quickly became obsolete. The Sun reports the closing of twenty eight of the 42 mills: "with the Allies now in control of the Mediterranean and the submarine menace defeated in the Caribbean, the shortage of rope materials could be overcome by importing of hemp from Central America and jute from the Mediterranean lands." (The "hemp from Central America" would be sisal, from the Agave cactus, and possibly also "Manila hemp" or abaca, a relative of the banana that had taken a large share of cannabis hemp's maritime markets. "Hemp" is often used generically for any long bast fiber other than flax.)

At the end of the war, the mills were either auctioned off or briefly leased to private operators, as was the mill at Union Grove. On May 16, 1945, the Sun reported that contracts had been signed for 1200 acres of production. The military continued to stockpile fiber for a time after the war, but by 1947 price supports received as a strategic crop were discontinued and the Wisconsin industry subsided back to the stalwart Rens Hemp Company.

Following the war, the Narcotics Bureau was pressured to equalize its treatment of hemp industry as persons in Illinois who, just prior to the war, had suffered under its heavy regulatory boot to the point of collapse, began pointing to the light touch given Wisconsin. This caused the FBN to threaten the enforcement of a transfer tax on the Wisconsin industry. Until then, it had only been necessary to pay a dollar and send in the form.

Willard Rens told the author that their business was never visited by any drug agents. The 1937 Marihuana Tax Act caused them some additional paperwork, but it was not what caused him to close the doors on the company, finally, in 1958. That was a consequence of loss of markets to synthetics. Plastics of petrochemical origin replaced natural twines and carpet backing.

That Wisconsin was so little encumbered by what is generally, albeit erroneously, regarded as marihuana prohibition stemming from the Tax Act, can only be attributed to the tradition of progressive legislators Wisconsin maintained over generations in the LaFollette family. Thus Matt Rens wrote in 1945 to George Farrell at the USDA:

...We are very grateful that this amendment (HR2348) has now become law so that the Hemp Industry can carry on as we have done in the past years and the hemp grown for fiber purposes can be transferred from the grower to the mills without paying an additional transfer tax, which we were threatened with by the letter received from the Narcotics agents.We wish to take this opportunity to thank you for the part taken in helping us put this across. Personally, we are convinced that the hemp industry should be kept alive for our national welfare and if this amendment had not been made and Mr. Anslinger [Federal Bureau of Narcotics Director Harry Anslinger] had had his way the hemp industry would have been killed.

The Rens Hemp mill

Highway 49, Brandon, Wisconsin

Willard Rens, now [1998] retired in Arizona, is the last commercial processor of hemp in America. The last crop was in 1957. Although association of his crop with marihuana was making it increasingly unpleasant to be in the business, it was competition with other fibers, natural and synthetic, and the failure to diversify uses that ultimately resulted in the demise of the Wisconsin industry. The actual prohibition of all cannabis, fiber hemp and marihuana, comes with the system of drug schedules established by the Drug Enforcement Administration in 1972, years after the last crop was grown, that categorizes plants with any detectable amount of the chemical THC as marihuana. In the fifties, the marihuana affair was a petty nuisance, no more, to the Wisconsin growers.

What was most critical was still the labor component for a crop with markets too small to capitalize major technological innovation. In a recent interview with men from the Waupun area reminiscing on the hemp industry they worked in, one of the men (John Lammers) recalls that the hemp was handled eleven times between cutting and shipping. It remained a labor intensive crop while its markets were eroded by the panoply of new synthetics.

In the past few years, several changes have altered hemp's prospects, heralding the imminent return of the crop, including:

- the current fiber shortage;

- increasing paper consumption;

- environmentalist pressure to curtail the harvest of "fossil" forest fiber;

- concern about the environmental impact of chemical herbicides; -recognition of cotton's chemical dependency;

- changing generational attitudes;

- growing markets for imported hemp-based goods.

Twice in 1995, researchers, marketers, educators, policy makers and environmentalist gathered in the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture-sponsored North American Industrial Hemp Forum [later: "...Council," NAIHC] to discuss the potentials and obstacles for "industrial hemp," as it is now termed. It seems highly probable we will be seeing fields of hemp in Wisconsin again.

Twine will not be the major use for the fiber this time. It is more likely to be used in paper and resin-bonded construction lumber, as an extender to recycled paper and a reinforcer for straw-based composites, and to some degree, textiles. [2013: Hemp is coming back in an entirely new guise. The bast fiber may become the by-product. Hurds are being used in "HempCrete" or "HempStone® construction. But the real ascendant product of the hemp plant is its seed, the high protein meal and the nutraceutical oil.]

The return of hemp to the farmer's repertoire has hurdles to overcome, as our situation is rather like that of a century ago.

- We have lost the know-how for farming this crop.

- But the hemp of the future will require new approaches, so we are freed from antiquated practices.

- We have lost the machinery.

- But, new machines would be needed, regardless. Today we have hydrostatics.

- We have lost the germplasm.

- Uh-oh!